Annotating The Hobbit: Chapter One

The power of enchantment, wonder, and recovery in The Hobbit

Welcome to the first of my Hobbit Annotation series, where I’ll be sharing and expanding upon my annotation notes as I reread J.R.R. Tolkien’s The Hobbit. Today we’re diving into Chapter One: An Unexpected Party.

This series is for any who wish to step into the text of The Hobbit, whether its been a while since you’ve read the book, or you’re currently reading it! Read along with me and feel free to contribute to the conversation in the comments section!

An Unexpected Fairy Tale

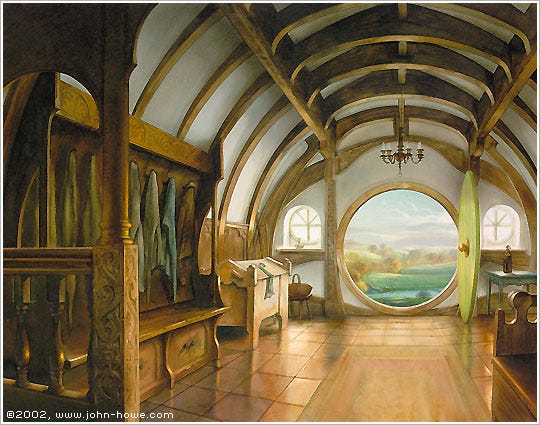

With the famous first line of “In a hole in the ground there lived a hobbit” (1), Tolkien begins The Hobbit with an almost classic fairy tale opening. Though he might not use the words “once upon a time,” Tolkien undoubtedly sets up an introduction that feels similar, with “there lived a hobbit” signaling just as strongly that a story if the fantastic is about to begin. Just as fairy tales are usually set in a world that is at once both familiar to and distant from the one we know, so too does The Hobbit resemble a mix of both familiar and unfamiliar elements.

With Bilbo’s home described as being “a comfortable tunnel without smoke, with panelled walls, and floors tiled and carpeted”(3), the reader is instantly in a comfortable, familiar space, perhaps having only to look up past the pages of their book to instantly find themselves in a similar setting as Bilbo’s “bedrooms, bathrooms, cellars, pantries” (3). Yet in the midst of this familiarity is the underlying question of the titular—and unfamiliar—Hobbit mentioned in the very first sentence. What is a hobbit and who is Bilbo?

The narrator jumps into explaining this, but retains a fairy tale like distance in doing so. Traditional fairy tales are not set in any particular time frame (hence the “once upon a time” or “there was and there was not” opening of fairy tales) and the narrator of The Hobbit is careful to describe the story’s setting as similarly outside a recognizable time frame. With the story starting with “By some curious chance one morning long ago in the quiet of the world, when there was less noise and more green, and the hobbits were still numerous and propserous…” (5), the narrator intentionally sets the action of The Hobbit in a classically indeterminate time period, similar to that of traditional fairy tales.

The narrator further maintains this fairy tale-like storytelling by reminding the reader of the act of storytelling as well the act of their own participation in interpreting meaning from the story:

“This is a story of how a Baggins had an adventure, and found himself doing and saying things altogether unexpected. He may have lost the neighbour’s respect, but he gained—well you will see whether he gained anything at the end” (2).

A Tookish Calling

Certainly there will be more instances of fairy tale elements in The Hobbit (there must be whole papers or presentation on this!), but as we move on in this first chapter of Hobbit annotations, the next most striking thing to me is the contrast between Bilbo’s Took and Baggins ancestry. We’re told that there was “something a bit queer in his make-up from the Took side, something that only waited for a chance to come out” (5). This “queerness” of the Took side is likely due to one of Bilbo’s Took ancestors taking “a fairy wife” (5) and going on adventures and is set as a contrast to Bilbo’s Baggins side of the family, who reportedly stayed put in their comfortable hobbit hole where “they remained to the end of their days” (5).

Setting up the Took and Baggins side of Bilbo in this way, the narrator immediately invites the reader to examine their own relationship to adventure and magic. Will you be ready for adventure? Do you have a Tookish side waiting to be awakened? The reader is primed to be ready to take on—or at the very least think more deeply about— their own readiness for the forthcoming adventure.

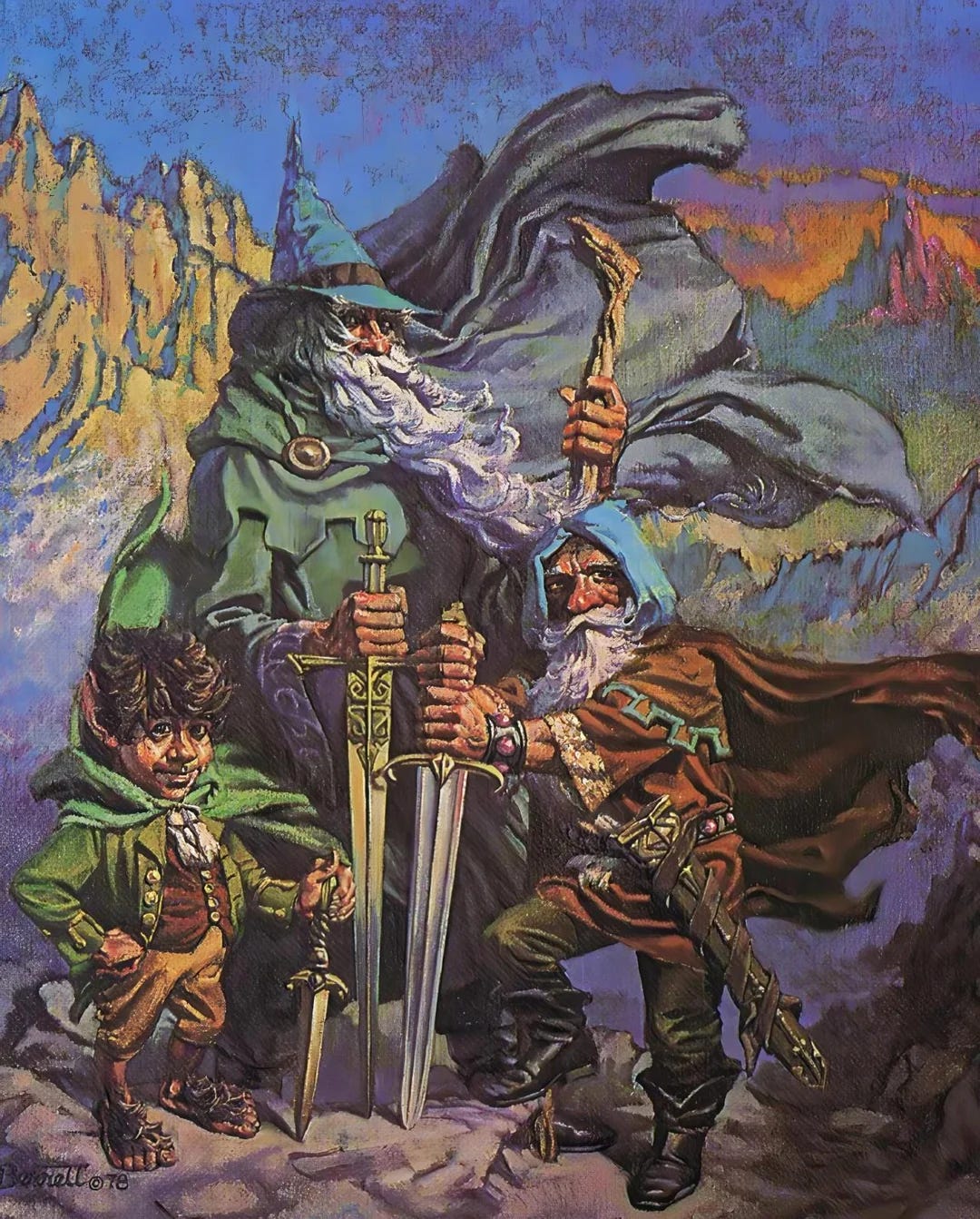

“I am Gandalf, and Gandalf means me!”

When we are first introduced to Gandalf in The Hobbit, it is not through a description of his physical appearance (though that does come), but by his strong association with tales and adventure:

“Gandalf came by. Gandalf! If you have heard only a quarter of what I have heard about him, and I have only heard very little of all there is to hear, you would be prepared for any sort of remarkable tale. Tales and adventures sprouted up all over the place wherever he appeared, in the most extraordinary fashion” (5-6).

The narrator not only immediately links Gandalf to adventurous tales, but creates a sense of enchantment in doing so by showing their own elation and wonder of Gandalf. It’s almost as if the narrator can’t help the exclamation of “Gandalf came by. Gandalf!”: a reaction that Bilbo shortly echoes when he too exclaims Gandalf’s name and promptly recalls the legends and tales associated with him:

“Gandalf, Gandalf! Good gracious me! Not the wandering wizard that gave Old Took a pair of magic diamond studs that fastened themselves and never came undone till ordered? Not the fellow who used to tell such wonderful tales at parties, about dragons and goblins and giants and the rescue of princesses and the unexpected luck of widows’ sons? Not the man that used to make such particularly excellent fireworks! I remember those!… Not the Gandalf who was responsible for so many lads and lasses going off into the Blue for mad adventures?” (7-8).

Thus the reader is not once, but twice, given strong associations of magic, adventures, and legends in their introduction of Gandalf. More than that, the reader experiences twice over the feeling of enchantment through the experience of another. While we may not know details of Gandalf’s character at this point, it seems that we’re meant to have a very clear understanding of how we should feel encountering him.

Bilbo’s Enchantment Through Song

Throughout the first chapter of The Hobbit, Bilbo struggles with his adventurous Tookish side waking up alongside his ordinary, “I don’t want any adventures, thank you” Baggins side. He has to stop himself from being too Tookish while speaking to Gandalf: “Bless me, life used to be quite inter—I mean, you used to upset things badly in these parts once upon a time” (8). The Tookish side peeks through here, showing that even though it may be dormant in his day to day hobbit life, Bilbo does have a desire for the magical over the mundane.

This is hard for him to admit, however, and as the dwarves assemble in Bag End, we watch as Bilbo goes from being dismissive of the adventure at hand to finally accepting it. I’ve always read this scene as Bilbo rather straightforwardly denying his Tookish side, but this time around, I’ve realized there are subtle shifts in Bilbo’s reactions the show just how much Bilbo has to try to push down his natural Tookish inclinations.

Bilbo is at first dismissive as he senses adventure. The dwarves “sat around the table, and talked about mines and gold and troubles with the goblins, and the depredations of dragons, and lots of other things which he did not understand, and did not want to, for they sounded much too adventurous” (11-12). Here, Bilbo distances himself not only from the dwarves and their adventures, but also from his own relationship to (and knowledge of!) tales of goblins and dragons. We know Bilbo has heard all sorts of adventure tales—he was excited by them when talking to Gandalf! Yet he denies his knowledge or desire to understand them here.

After “no other than the great Thorin Oakenshield” (13) arrives, however, Bilbo begins suspecting that adventure is closer at hand than ever: he “was beginning to wonder a most wretched adventure had not come right into his house” (14). But no sooner does Bilbo begin to accept the possibility of adventure than he actively denies his part in it. We watch Bilbo “trying to look as if this was all perfectly ordinary and not in the least an adventure” (14). If he cannot deny that an adventure has arrived in Bag End, then Bilbo can at least deny his part in it thus far.

These moments show Bilbo very purposefully and willfully distancing himself from the idea of adventure. However, as we will shortly see, Bilbo’s much more inclined to feel enchantment of the wider world and desire for adventure—to be aligned with his Tookish side— than he wants to believe.

As the narrator mentioned earlier in the chapter, the Tookish side of Bilbo has only been waiting for a chance to come out. It seems that chance, at least for Bilbo, best presents itself through tales, stories, and music. It’s through these in which Bilbo can feel inspired, excited, and above all—enchanted.

And I love how the narrator sets the scene for Biblo’s enchantment of the dwarves’ music and song. As soon as Thorin starts playing his harp, Bilbo is transported into the world of the dwarves by music that was “so sudden and sweet that Bilbo forgot everything else, and was swept away into dark lands under strange moons, far over The Water and very far from his hobbit-hole under The Hill” (16). Through the dwarves music, Bilbo and the reader alike are invited to leave Bag End and enter the wider, unknown world, to trade familiar comforts for things strange and new.

The narrator continues:

“The dark filled all the room, and the fire died down, and the shadows were lost, and still they played on. And suddenly first one and then another began to sing as they played, deep-throated singing of the dwarves in the deep places of their ancient homes; and this is like a fragment of their song, if it can be like their song without their music” (17).

With a darkened room and the idea of ancient dwarven history and magic evoked, the dwarves begin to sing. But their song is more than just words to accompany their music: it is an act of storytelling in and of itself, telling the story of the dragon Smaug and the plight of the dwarves in seeking to reclaim their home. Transported elsewhere through music and inspired by the song’s storytelling, Bilbo’s heart is awakened to magic and adventure:

“As they sang the hobbit felt the love of beautiful things made by hands and by cunning and by magic moving through him…Then something Tookish woke up inside him and he wished to go see the great mountains, and hear pinetrees and the waterfalls, and explore caves, and wear a sword instead of a walking stick” (19).

Suddenly Bilbo finds himself craving exploration, danger, and adventure in the wild world. By all means, he is enchanted.

Recovery through The Hobbit

One final note about Bilbo’s enchantment here before we end this chapter. I can’t help but think of Tolkien’s notion of Recovery while reading this. The idea of Recovery comes from Tolkien’s “On Fairy Stories,” a lecture in which he discusses the nature of reading and writing fairy stories and fantasy. In relation to recovery, Tolkien suggests that while the familiarity of our world can lead to a sort of apathy, 1 reading fantasy can reawaken our hearts to seeing the world anew:

“We should look at green again, and be startled anew (but not blinded) by blue and yellow and red. We should meet the centaur and the dragon, and then perhaps suddenly behold, like the ancient shepherds, sheep, and dogs, and horses— and wolves. This recovery fairy-stories help us to make.”

Reading fairy stories and fantasy gives us the ability to reawaken our childlike hearts and see the world fresh once more. The example I like to give when discussing Tolkien’s idea of Recovery is that after reading about Ents in The Lord of the Rings, you might have a new perspective on trees afterwards. Maybe the next time you see a tree, you think of Treebread and see a sort of magic in the real world that you otherwise wouldn’t have. This is the power of fairy stories. Fantasy and fairy stories present our familiar world as new, strange, and exciting. And after experiencing fantasy, we can then look to our own world and find a sort of newness there.

I think Bilbo experiences this sort of recovery after hearing the dwarves’ song:

“The stars were out in a dark sky above the trees. He thought of the jewels of the dwarves shining in dark caverns. Suddenly in the wood beyond The Water a flame leapt up—probably somebody lighting a wood-fire—and he thought of plundering dragons settling on his quiet Hill and kindling it all to flames” (19).

Where Bilbo might have looked at stars previously and seen the same stars he always had, he now looks upon the stars and thinks of dwarvish jewels. An ordinary fire that he otherwise might not have had a second thought about, spurs up an image of a dragon’s fire. Though this is just the start of Bilbo’s exposure to adventure—his very own fairy story—he already begins to experience a sort of recovery of his mundane and familiar world.

The Hobbit begins with the familiar, the ordinary, and the comfortable. After all, Bilbo’s home is “a hobbit-hole and that means comfort” (3). But throughout this first chapter, Bilbo is pushed to expand his thinking beyond what he is familiar with, pushed to lean into his adventurous spirit and pushed to allow himself to be enchanted and transported—literally and figuratively—from all that is familiar to him. By the chapter’s end, Bilbo falls asleep with the dwarves song in his ears which gives him “uncomfortable dreams” (31). As with all good fairy stories and adventure tales, The Hobbit whisks us away from our comfortable, ordinary world. And though we, like Bilbo, are venturing into a world more uncomfortable than the one we know, may we all be as lucky to experience enchantment and recovery along the way.

I hope you enjoyed this annotation expansion (turned into somewhat of a deep dive) on Chapter One of The Hobbit. I’m sure not all chapter notes will be this long, but I’d love to move on to chapter two. Let me know if you want to see this series continued and please consider a paid subscription to help support my work!

Smaller Notes on Chapter One:

Coffee in middle-earth! Is this the only mention we have of coffee? “A big jug of coffee had just been set in the hearth” (12). Just fun to think about.

The dwarves “chip the glasses” song shows their sense of humor and lends some levity to the chapter that I think is a lot of fun to experience.

The subtle magic of smoke rings: “wherever he told one to go, it went….Bilbo stood still and watched—he loved smoke rings” (16). Perhaps a smaller, but still important moment of enchantment for Bilbo.

When Bilbo decides to go on the adventure he declares, “Tell me what you want done and I will try it, if I have to walk from here to the East of the East” (22). I love this determination in Bilbo and can’t help but feel that this moment echoes Bilbo offering to destroy the ring during the Council of Elrond chapter of The Lord of the Rings.

“We say we know them. They have become like the things which once attracted us by their glitter, or their colour, or their shape, and we laid hands on them, and then locked them in our hoard, acquired them, and acquiring ceased to look at them.”— Tolkien, “On Fairy Stories”

Seems like a good time to reread The Hobbit 😌

I know this tale as “there and back again”, and I am quite sure the Red Book in my keeping is the original. I’m pleased that you Big Folk enjoy our hobbitish ways!